I found the few surviving pages of C. James Crysler’s WWII journal buried in a wooden trunk in his son’s basement – a choice man cave filled with old carpentry tools, hunting gear, a huge flat screen TV, one partially restored 8mm film projector, and a collection of military records and combat medals earned by both father and son in two American wars fought three decades apart. There are only 11 handwritten pages left in his war-diary, but it reads like the classic Hollywood script for a young Jimmy Stewart: the improbable delivery of a new B-25 bomber from Florida to India by a freshly-minted pilot and his crew, including a scene in a seedy Brazilian night club filled with German soldiers after his dangerous trans-Atlantic crossing. It is the defining record of his perilous journey, and the beginning of his heroic tale.

——————————

– The War-Journal of Lt. C. James Crysler –

“To recall accurately the events that have happened since May 5, 1942 when I left Morrison Field is impossible, so I will state them as I remember them.”

“The night of May 4th was beautiful—the stars were bright and the weather ideal for our planned flight. I had tried to catch some sleep in the afternoon, but with thoughts of the coming mission sleep was impossible.”

“The ship was ready for flight with bomb bay tanks installed, guns loaded and provisions for an over water flight securely loaded on. We had studied our route with our navigator Lt. Arvis R. Kirkland, and checked and double checked every detail of the plane’s equipment and the many small details that needed attention before take-off.”

“We were loaded with maps, intelligence reports, weather data, codes, etc…and finally the food, which we enjoyed all the way to India. Our crew chief, Sgt. Ralph J. McCann, had checked our motors for days and they were in excellent condition.”

“Lt. John C. Ruse and myself, who were to pilot our B-25, had checked thoroughly on our crew to make sure we could depend on them. Sgt. Delbert E. Coulter, our bombardier, was the least experienced and had trouble operating the new turrets, and was not too good on the bomb sight. Cpl. William P. La Plant is an excellent radio operator and during the whole trip proved of inestimable value.”

“With this crew of six we were ready for this new adventure which we all looked forward to with great enthusiasm. Successful flights to Cuba and back gave us confidence in our navigator and we anticipated a successful trip to our final destination.”

——————————

——————————

“Shortly after midnight we climbed aboard and started our motors. We cleared with the tower and kissed Palm Beach good-bye. We called our ship the “Yokahama Express,” and we roared down the runway with the heaviest load we had ever attempted. We managed to get it off the ground, and in a few minutes we were on our way out to sea. It was the most exciting moment I think I’ve ever had in an airplane—that moment when the lights of West Palm Beach were fading in the background and we were headed out over mysterious waters.”

“The following morning was bright, the sky clear and visibility good. The trip to Wallerfield, Trinidad took ten hours and twenty minutes and was uneventful. Our crew chief had served us breakfast of coffee and sandwiches. I was tired and sleepy as the sun had shown in my face for hours, and the continual drone of the motors had numbed my ears.”

“We passed over Port of Spain, where a huge convoy of merchant-men had gathered. At Waller it was hot and sticky and we refreshed with a cold shower. We slept all afternoon, and that night headed out again for Brazil.”

“In the early morning hours we passed over Devil’s Island and buzzed the place against orders. This was a French possession and we were to stay at sea, but the temptation was too great.”

“The flight to Belem was eight hours, and about two hours out we ran into a tropical storm and had to fly about 20 feet off the water. This cleared up and we passed over dense jungles. We had our first real glimpse of primitive life. We had good sport buzzing the trees and scaring the natives who had probably never seen a plane. Belem was hot and humid and we had our first look at a Brazilian.”

“We gassed up our tanks and watched carefully for any signs of sabotage. We had to wait a day so, and then left Belem the following morning and in five hours and fifty minutes we were in Natal, the jumping off point for Africa. Natal is a dirty town and filled with spices. The main hotel in town where we stopped to get a drink was jammed with Germans. The sight of them made us dislike the place even further.”

“The first flight of four B-25’s had taken off two nights before we had planned to leave and reports we received were discouraging. One had gone down at sea in a storm and one had landed at Dakar in French territory and was interned (They had turned on a powerful D.F. and drew them in there). Another one ran out of gas and landed on the beach on the Nigerian coast, and finally one had succeeded and had landed safely at Roberts Field.”

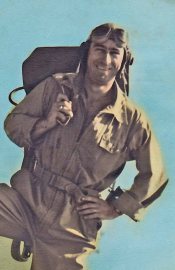

Lt. Tom Harmon (on right), winner of the 1940 Heisman Trophy, standing next to his P-38G, “Little Butch II”

“Hearing this news caused us to take further precautions. We dismantled our armor plates and dropped our extra food supplies, which we turned over to the Brazilian Coastguard. We also left our bombardier and his supplies behind, along with every other pound of unnecessary equipment. We had to wait until dark planning our arrival on the African coast after the fog had lifted.”

“While we waited that last afternoon we toured the local airport and vicinity and more or less inspected the local Brazilian Army or guard outfit that was stationed here to protect the base. Three or four German and Italian planes were hangared at Natal but were inoperative. We wondered how long it might be until we first met them in the air.”

“After supper we were briefed by the base commander and were given all the necessary information we needed for the flight to our next stop. We talked to several ferry pilots who had made the trip before, along with a few Pan Am pilots, and accumulated all the advice at their disposal.”

“I can’t leave South America without noting that here was a place where you could buy all the tires you wanted and cheap at that, while at home it was becoming more impossible every day to get your hands on one.”

“By eight o’clock on the evening of May 10 we were in our plane warming up the motors, and about 10 minutes later we were in the air to be the first of our flight headed across the South Atlantic for the first time. To us, it seemed the most hazardous leg on the route, and I prayed for those engines to keep running.”

“The weather was clear with about a 4/10 overcast when we left at about 5000 ft. We climbed to 8,000 ft. and had perfect weather most of the night and the sky was jammed with brilliant stars to help our navigator. We instructed him to double check every plot as we hoped not to use our D.F. as Dakar wasn’t far off our course and we had no intention of landing there.”

“About 2 A.M. we sighted a gathering of lights and the water below. It could have been our navy or the enemy gassing up or submarines being tended. As we approached the lights went out and it was impossible to make out first what was there.”

“About 500 miles off the coast we ran into a pounding storm and flew on instruments for about an hour. Hail stones battered the ship and rough air tossed us around the sky. That was probably the most unpleasant part of the trip. We had been conserving gas by using minimum manifold pressure, R.P.M. and mixture, cruising at 164 M.P.H. Now we were forced to adjust the power to the engines to maintain altitude and control of the plane. When we had passed the worst of it, our navigator could again go to work occasionally and we hoped we were still near our course.”

“I think I know how Columbus felt when he saw land. The coast line was a heavenly sight and the fog had completely lifted. Our next worry was if we were north or south of Roberts Field, Nigeria. We turned south, and in about 10 minutes found the field, having missed it by about fifteen miles. That was the best work Kirkland had ever done in his life as far as we were concerned. We circled and landed after 14 hours and ten minutes in the air.”

“Tommy guns were everywhere, and we had an…”

——————————

The journal ends there. Crysler eventually made his way safely to Dinjan, India on June 2, 1942. The next day, after a successful bombing raid over Burma, he and his crew was being pursued by the enemy when they ran out of fuel and had to bail out of their B-25. The survivors made their way through the dangerous jungle to safety, and Crysler ended up in Kunming, China where he ended up flying 15 combat missions with the American Volunteer Group’s legendary “Flying Tigers” from mid-June through early July of 1942.

When the Flying Tigers disbanded on July 4, 1942, he joined the 74th Fighter Squadron and flew 68 more missions throughout the China/Burma/India Theater, logging in over 200 total combat hours. After the war, he signed up as an officer with the newly created United States Air Force. Lt. Col. C. James Crysler received his honorable discharge on 31 March 1961 after 20 years of military service. – Cliff Davids

——————————

——————————

The author has provided the reader with an exciting introduction to the story of two heroes–a father and a son–who put their lives on the line during two different wars. The father, C. James Crysler, set the standard while fighting the Japanese during WWII. His son Ron, using his father’s courage and bravery as a guide, also served his country with honor and distinction during Vietnam.

I know the son very well, and I met the father in 2005. It was my privilege to set up a meeting at that time between Ron and James Crysler and the daughter, granddaughter and daughter-in-law of General Claire Lee Chennault, founder and commander of the Flying Tigers.

I never met Ron’s father, James Crysler, but I have known his son Ron for over 40 years. He graduated tops in his flight class and was held back as a flight instructor in the Naval Advanced Training Command, flying the 2 seat A-4 Skyhawk (TA-4J). He was a well-liked individual with a friendly demeanor.

After his tour as a flight instructor, Ron went on to fly the A-7 Corsair ll, a light attack carrier based fighter-bomber. He flew over 100 missions during the Linebacker operations (bombing North Vietnam) to force the North Vietnamese back to the peace negotiating table. Ron continued his flying career and retired as an airline pilot. His friendship is considered an asset to those who know him.