The following interview with C. James Crysler first appeared in the January 28, 1944 edition of the “Curtiss Wright-er,” the newsletter for the Curtiss-Wright Corp., maker of the rugged P-40 Warhawk. Although I never met Crysler, this interview paints the colorful portrait of a high-flying 27-year-old WWII fighter pilot who had just returned home on furlough. He later went on to become a USAF Command Pilot and a dedicated family man. He spoke openly about his war exploits, and he never forgot about his service with the 1st American Volunteer Group, otherwise known as the legendary “Flying Tigers.” After he died, he gave his service records to his son Ron. Perhaps he knew they would provide the proof he might need one day to claim his rightful spot on the AVG roster.

——————————

“Japan’s Best No Match For P-40, Veteran of China War Declares–Capt. Crysler Relates Tales of Far East Action”

Japan’s best airplanes are no match for the Buffalo built Curtiss P-40 fighters in spite of their numerical superiority, according to Captain C. James Crysler, of 27 Somerton Avenue, Kenmore, whose 62 combat missions as a member of the 74th Fighter Squadron in China qualify him as one who knows whereof he speaks.

Captain Crysler, whose specialty was ground-strafing and dive-bombing in China and Burma during his 14 months in that theater, is spending a brief furlough with his parents at the Kenmore address pending reassignment. Credited with three Zeros and a probable fourth—all shot down during one two-hour dogfight over Kunming—he is also the holder of the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and the Chinese Order of the Cloud. Mandated as a second lieutenant in the air force in March 1942, Capt. Crysler was assigned as a pilot for a B-25. He ferried the ship to a base in India, and after a brief training, loaded it with bombs and took off for China.

The plan was to drop the bombs on a Japanese concentration in Burma, and despite bad weather and Japanese Zero squadrons, that objective was achieved. Captain Crylser arrived in China, all right, but a week behind schedule and without his airplane, which had been dubbed the “Yokahama Express.”

“The Japanese tackled our bomber squadron over the mountain after we had pasted the target,” Capt. Crysler explains. “The boys tried to hide in the clouds and I pulled my ship up over the overcast. I didn’t want to run into any mountains down in the soup. But we got lost, ran out of gas, and finally I had to give the order to bail out.”

Crysler, his navigator and his bombardier were the only members of the crew of the “Yokahama Express” to escape injury when they parachuted down into the unfriendly mountains of the Burma-China border. The trio started walking.

“We lived on bird’s eggs for seven days,” he relates. “Finally we stumbled on an outpost of the Chinese radio warning net system and they called for help. The boys at our new China base sent a light plane down and ferried us home.”

So there was Crysler—a bomber pilot without a bomber and with very little prospect of getting one right away. It didn’t take him long to decide what to do. On June 12, 1942 he started flying with the American Volunteer Group’s “Flying Tigers,” that group of flying daredevils equipped with Curtiss P-40’s.

On July 4, the American Volunteer Group was disbanded and many of its personnel went over to the 14th U.S. Army Air Force, under command of Gen. Claire Chennault, founder and leader of the “Tigers.” Crysler was one of them, flying a P-40 with the 14th Air Force’s 74th Fighter Squadron.

——————————

——————————

74th Fighter Squadron

That outfit was a Jack of all trades, to hear Crysler tell it. “We did ground-strafing, dive-bombing, bomber escort work, and general interception jobs,” he says. “The most fun was Burma Road strafing. You ought to see the enemy run when we come down to the Burma Road. They have no place to run to, though. We raised plenty of hob with their trucks, cars, and supplies in the Burma Road canyons.”

The high point of Crysler’s combat action occurred on May 15, 1943, when the warning net notified his base in Kunming that a “heavy force” of Japanese bombers escorted by Zeros was on its way in.

“Three of us with our P-40’s took off to intercept,” he declares. “We got some altitude and finally spotted them below us, on their way to Kunming. There were about 70 Japanese fighters and bombers, so we knew that we were going to have our hands full—at odds of about 23 to 1.”

“We gave our Hawks the juice and swung around so that we were on their tails, with plenty of altitude. We started our pass. On the first dive I nailed one Zero and he quickly spun out of the formation, but because he was not in flames and I didn’t see him hit the ground, he was only listed as a probable.”

“Our tactics were to get altitude and then dive through the enemy formation, giving the ship we had picked out a burst on the way through. Then we would zoom around for more altitude and repeat the process. The ability of the P-40 to withstand the terrific speeds generated in those tactics, where the Zero would have folded up, prevented them from doing much about it.”

The sky battle went on for an hour, with the three P-40’s pecking away at the Japanese formation, before any help came from the field. And then it was only five more P-40’s flown by members of the companion 75th Fighter Group, but Crysler grins that this assistance was “enough to turn the tide.”

“We fought them halfway across China, but we saw that they had a good start for home,” he said. The fight had lasted for about two hours before Crysler’s ship ran out of gas and ammunition and he landed back at Kunming, with the scalps of three Japanese Zeros and the one “probable” hanging from his belt. “The other three planes were flamers, so I knew I had them for certain.”

——————————

——————————

“Hit and Run”

Crysler explains that the Japanese use a “beehive” formation, with Zeros constantly buzzing around the heavier, slower bombers located right in the middle. The “hit and run” tactics used by the P-40 pilots proved effective only because the Hawks were built sturdy enough to pull out of screaming dives at speeds in excess of 400 mph. He adds, “If the enemy had tried to dive with us, they’d lose their wings on the pull-out.”

Crysler says a squadron mate came up with a good example of the P-40’s ruggedness one day over Burma. “We were on a strafing mission, buzzing enemy ground troops, and this boy went just a little too low. He hit three trees, each probably three inches in diameter. One of the three trees smacked right against the spinner. Each of the others caught his P-40 on the inner panel of each side. Believe it or not, he mowed those trees down, pulled up, and made it back to the base. Part of the middle tree was still stuck in the cooler under the nose. There was a big dent in each leading edge. But the boys at the base fixed the ship in a few days. You could never survive a stunt like that in a Zero.”

Crysler fulfilled his earlier assignment as a bomber pilot, only at the controls of a P-40, when he was briefed to attack Japanese installations in Burma with 500-pound bombs. In addition to blasting troop concentrations, bridges, etc., he is credited with sinking two big supply barges on a river in Burma.

“We didn’t always run into aerial opposition, as our tactics were to hit and run at low altitudes,” he points out. “But the enemy on the ground made it plenty hot for us. No matter where we went, there were always a lot of people shooting at us. Their aim as a whole was pretty poor,” he adds. “But you always have to worry about some joker shooting at somebody else and hitting you by mistake.”

Nevertheless, Crysler came through the strenuous campaign with no injuries and his plane was never damaged.

For the past few months he was detailed to an advance base in India, teaching combat tactics to Chinese and American fighter pilots. These lads, equipped with the latest model P-40 Warhawks, are “going to make it plenty hot” for the Japanese, Crysler believes. They are being taught the “know-how” of aerial combat by men who learned it the hard way in Burma and China, and by the time they tangle with the enemy they’ll be well prepared to give a good account of themselves, he says.

Before he went to Nevada to study mining engineering back in 1937, Capt. Crysler worked in the mailroom at the Curtiss Kenmore plant.

——————————

–23rd Fighter Group–

——————————

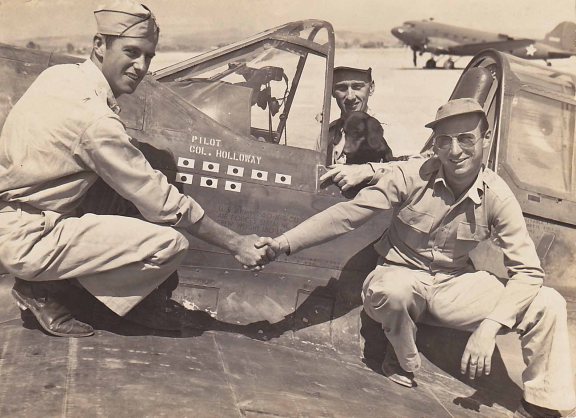

Lt. C. James Crysler (right), on May 15, 1943 in Kunming China, serving with the 23rd Fighter Group, 74th Fighter Squadron of the Flying Tigers. He had just shot down 3 confirmed and 1 probable enemy aircraft in his P-40E. Also pictured are Lt. Col. Bruce K. Holloway (center) with his dog Joe, who had one zeke and one bomber, and Maj. Roland M. Wilcox (left), who had 3 confirmed and 2 probable.

——————————

(L-R) Robert L. Scott, Arvid ‘Ole” Olson, Cliff Groh, Col. Lin Wen Kway. Charles J. Crysler is second from the right. Pilots with the 23rd Fighter Group relax after a combat mission. (Photo from Air Life)

——————————

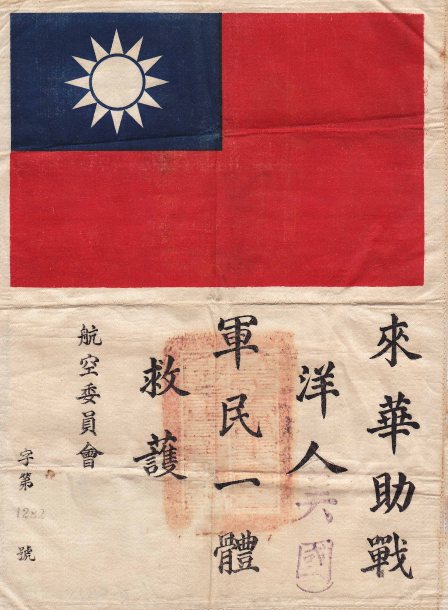

“Blood Chit” (serial #1282) issued to Lt. C. James Crysler. It states: “This foreign person (American) has come to China to help in the war effort. Soldiers and civilians, one and all, should rescue, protect, and provide him medical care.”

——————————

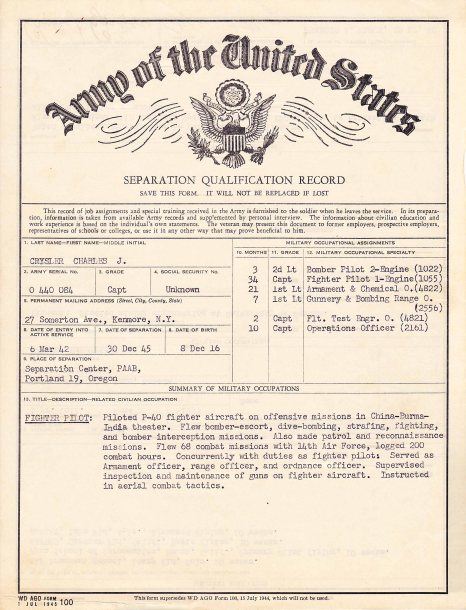

–Army of the United States–

“Separation Qualification Record”

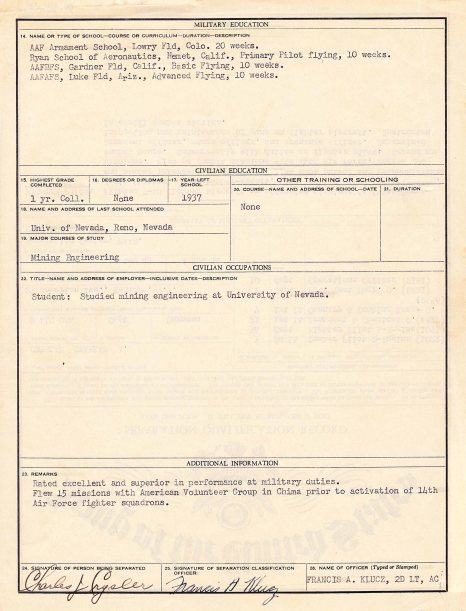

“Rated excellent and superior in performance at military duties. Flew 15 missions with American Volunteer Group in China prior to activation of 14th Air Force fighter squadrons.” (page 2, section 23)

——————————

(All photographs and documents are from the Crysler Family Collection)

——————————

Cliff, this is an excellent and accurate story about my father, the young Capt. C. J. Crysler. I am his oldest son and a former Navy attack pilot who flew A-7’s during the Vietnam War. We spent thousands of hours together trading war stories with each other. One of the many things we had in common was that we had both bombed Hanoi, North Vietnam: Dad in 1942 and his son in 1972. His P-40 could carry one 500 lb. bomb and my A-7 could carry twenty-four 500 lb. bombs. Keep the great stories coming. — Ron Crysler

Ron: Thank you for sharing your father’s story with me – his many adventures make for an exciting read. Perhaps one day we’ll read about your own exploits during the war in Vietnam.

Cliff, I loved reading these stories–I remember hearing a few of them as a young child. To see my grandfather’s story here along with those old photographs really brings it back to life. When I first heard them, I wasn’t able to fully appreciate the magnitude of what he had done. Great job!

As the granddaughter of General Claire Chennault, it is with a sense of pride that I read this story. My grandfather was so blessed to have such courageous men under his command. With his tactics, and their zeal and bravery, they were truly a force to be reckoned with.

As Director of the Chennault Aviation and Military Museum, it is my honor to have these stories included in our collection. I will make a copy and include it in our personal accounts of the brave men who flew for China. Thank you for sharing, and I hope that we can continue to let the American people know the sacrifices that have been made on our behalf.

Sincerely,

Nell Calloway, Director

Chennault Aviation and Military Museum

Monroe, Louisiana

THE FLYING TIGERS AMERICAN VOLUNTEER GROUP: THE MOST ELITE FIGHTER GROUP OF ALL TIME!

REF: (L-R) Robert L. Scott, Arvid ‘Ole” Olson, Cliff Groh, Col. Lin Wen Kway, Joe Rosbert, unknown, C. J. Crysler, unknown. Pilots with the 23rd Fighter Group relax after a combat mission. (Photo from Air Life)

This caption for the above photo incorrectly identifies Joe Rosbert as the fifth gentleman from the left. Although my father knew several (if not all) of the men in the photo, that is not Joe. I do not know who that is. I wish I could help you identify him but, in my research, I haven’t been able to do so.

Robert Rosbert

(son of Camille Joe Rosbert)

Thank you for letting me know. I have made the appropriate change to the caption beneath the photograph.