Two months after the crash of Southern Airways Flight 242, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) conducted a five day public hearing at the Sheraton-Biltmore Hotel in Atlanta, GA. The witnesses included crash survivors, internal investigators, engine specialists, air traffic controllers, meteorologists, and a host of other experts directly involved with the crash investigation. Their testimony highlighted the series of fatal mistakes that led to the accident on April 4, 1977, claiming the lives of 63 people on board and nine others on the ground.

One of the prime miscues occurred 16 minutes into the flight from Huntsville, AL to Atlanta, right after the plane lost thrust in both engines in a hail storm over Rome, GA. The captain of Southern 242 had requested that the flight controller at the Atlanta Air Route Traffic Control Center in Hampton, GA provide him with a vector to Dobbins Air Force Base in Marietta, GA. Dobbins had a 10,000 foot runway that gave the copilot a fighting chance to make a successful forced landing.

Instead, he was instructed by the control center in Hampton to switch to a new frequency and contact Atlanta Approach Control at Hartsfield International Airport in Atlanta, GA for the vector – but the pilot was unable to get through due to frequency congestion. The aircraft then lost electrical power to the AC busses for a second time, losing all radio contact for a period of 2 minutes and 4 seconds.

The flight crew could have reopened communications through their number one radio by activating the aircraft’s batteries using the emergency power switch. The navigational equipment would have become fully operational, allowing the crew to “dead stick glide” in flight instrument conditions towards the intended forced landing site at Dobbins. No one knows why the pilots failed to activate the emergency power, but they remained out of contact for those critical few minutes until the auxiliary power unit (APU) was restarted and communications were once again restored.

It was during that brief period that the pilots made an unexplained 180-degree turn while the plane dropped from an altitude of 14,000 feet to 7,000 feet, heading away from the Dobbins AFB and west towards Cedartown, GA. The flight controller at the control center in Hampton, who had by then turned control of Flight 242 over to Atlanta Approach Control, said that he thought the pilots were going to try and make a forced landing on the 4,000 foot runway at Cornelius Moore Airport in Cedartown, a few short miles away.

At that very same moment, Robert St. Martin, the controller at Hartsfield, stated that he had felt helpless as he also watched the powerless aircraft on his radar make the unexplained change of course during the communications blackout. He later testified, “I watched the aircraft heading westbound and nobody was talking to him.” The FAA subsequently determined that the DC-9 could have reached Dobbins if the pilots had not made that 180-degree turn.

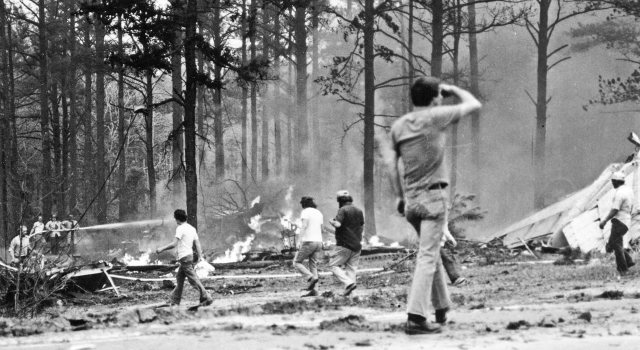

But when flight radio communications were re-established, the Hartsfield control tower provided the crew with a vector back to Dobbins AFB. St. Martin, who was now handling the powerless DC-9 from Hartsfield, stated during testimony that he was not familiar with the Cedartown airport because it was located just outside of the forty mile radius that comprised his range of responsibility. Tragically, the Hampton controller never relayed the information concerning the alternate runway at Cornelius Moore to either party. “We did not have control of the aircraft,” he testified, “Hartsfield had control of the aircraft.” Twenty-four minutes after take off, Southern Airways Flight 242 crashed and burned in rural New Hope, GA.

Robert St. Martin spoke candidly during the NTSB hearing, stating, “I was the last person to talk to the guy. At the time, I was hoping when he put it down on the highway it would work out fine because it was the only thing left to do. I knew we were getting desperate. The pilot was getting desperate.” After the crash, he said, “In my throat, I was barely breathing. In my stomach was a knot the size of a watermelon. I was all choked up. I went to the restroom and I was very disoriented.”

When the NTSB came out with their findings in January of 1978, they stated that the “probable cause” of the accident was the loss of thrust from both engines while the aircraft was penetrating an area of severe thunderstorms. The three major “contributing factors” were Southern’s dispatching system for the most up-to-date severe weather information, the captain’s reliance on airborne weather radar, and the severe limitations in the FAA’s air traffic control system for dissemination of weather information to the flight crew.

The air traffic controllers, who had come under such intense scrutiny during the NTSB hearings for their actions, were not included as a contributing factor in the final report. But for Robert St. Martin, the worst was yet to come.

——————————

The Southern Airways Flight 242 Crash Site

– New Hope, GA –

——————————

– The Legacy of Southern 242 –

At the time of the 1977 accident, Robert St. Martin was a 46-year-old flight controller with almost two decades of experience in the tower. Afterwards, St. Martin wasted little time and quickly returned to work. One year later, he was interviewed by a reporter doing a story for the anniversary of the crash. He spoke about the lawsuit he was involved in and the continuing criticism he faced, “Oh yeah. There’s been a lot of second-guessing, a lot of Monday morning quarterbacking. They’ve badmouthed me like crazy. You try not to let the thing bother you, but being human, you always have second thoughts.” He went on, “But I know the facts. I was directly involved. I thought I did the best I could. But it still eats at you. I’m not leading a normal life.” That was a major understatement.

What St. Martin didn’t mention to the news reporter was that between 1969 and 1973 his immediate family had experienced a series of terrible losses: the death of his father; the death of his older brother to cancer; the passing of his wife Darthie’s grandparents; and then the fatal shooting of his wife’s aunt by her former husband, who then turned the gun on himself and committed suicide.

But it didn’t end there. In February of 1976 his troubled stepdaughter Sheila, who had earlier run away from home, was discovered lying dead on a deserted highway in Florida. She had accused him of “making some advances” towards her, causing great difficulty in his marriage and family. An autopsy revealed that Sheila had been both pregnant and on drugs just before her death. It had devastated both he and Darthie, and things never returned back to “normal.” And then 14 months later he was the flight controller tracking Southern Airways Flight 242 when it crashed in New Hope. How could one man possibly handle such chaos and adversity? Still, St. Martin soldiered on.

Four more challenging years passed. As his marriage spiraled downwards, he began drinking more heavily. And then his work at Hartsfield assumed extreme proportions in August of 1981 when PATCO, the air traffic controllers union, went on strike seeking better working conditions and increased wages. Ever stubborn, St. Martin crossed the picket line and remained at work following the bitter strike and mass firings by President Ronald Reagan. His job in the control tower became even more stressful.

Nine months later, just weeks after the fifth anniversary of the crash of Southern Airways Flight 242, he finally snapped. When it was all said and done, his wife Darthie lay dead on the driveway in front of their house, her body riddled with bullets. Their neighbors found him with the gun, babbling incoherently over her corpse, wailing with such an inhuman intensity that they struggled to describe the sound to investigators. “It’s like something I have never heard before,” said one witness, “It was a high…it was just a no-syllable sound. Just a piercing screech, a pulsating type scream.” St. Martin was arrested at the scene and taken into custody.

Amazingly, he was released two weeks later after undergoing a psychiatric evaluation and posting a $50,000 bond. His mother-in-law had testified on his behalf at the bond hearing, stating that he was a good father and should be released so he could care for the former couple’s two teenage children. Two months later he was indicted by the grand jury on murder charges, and the case quickly went to trial in October of 1982.

St. Martin’s attorney Amy Hembree claimed her client suffered from temporary insanity at the time of the shooting due to his severe drinking problem, the couple’s long history of marital strife, their impending divorce, and his guilt over the horrific New Hope plane crash. “The marriage and the job caused him to snap under pressure,” Hembree informed the jurors, “he did not at any time of the (shooting) incident fully comprehend what was going on.” He testified on his own behalf, but the jury didn’t buy it. After four hours of deliberation, he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Incredibly, after serving only seven years and two months, Robert St. Martin’s sentence was commuted and he was paroled on December 13, 1989, retaining his full government benefits. He quickly disappeared from public view, and his story was soon forgotten. As for his wife Darthie, I have always considered her to be one of the uncounted victims from the tragic crash of Southern Airways Flight 242.

——————————

– The Crash Site/Then and Now –

——————————

What a tangled web of tragedy!

How right you are. D.H. Lawrence once wrote: “Tragedy is like a strong acid – it dissolves away all but the very gold of truth.”

I am an 8th grader at Dodd Middle School in Cheshire, CT and we are learning how to design podcasts and use other technologies as part of our communication class. As part of this project our teacher gave us the opportunity to learn about whatever topic we wanted to learn more about and I have chosen to learn about the truth behind horror stories and what makes them so realistic and scary.

Therefore, I was wondering if it would be possible to interview you about this topic as part of my podcast. I want to thank you for your consideration of this possible interview and look forward to hearing from you.

If you would like to check out some of our students past podcasts you can listen to them at the link below.

https://sites.google.com/a/cheshire.k12.ct.us/spartancast/podcasts

Thanks again for your time and consideration,

Jordan Nann

Jordan: Thank you for your interest. I checked out your site, and I can see that the talented students and teachers at SpartanCast Productions are creating excellent podcasts. Keep up the good work!

Unfortunately, I won’t be able to do an interview with you. Sorry. But you have chosen an important topic—searching for the truth behind “the truth” can take a challenging lifetime.

You have done well, telling a story that is more tragic than many people realize.

Thank you.